Horror fanatics spend a lot of time deconstructing the much-abused Final Girl. In position as the Last One Standing against every unthinkable monster lurking in the dark, her ability to survive is a badge of honor, but also a mark of what our culture values (or conversely, stubbornly refuses to appreciate) in young women.

Because the Scream series is a meta-narrative all about deconstructing movie tropes, Sidney Prescott’s journey has always been prime real estate for discussing and dismantling Final Girl stories, a role that she has undertaken with all due pain and a crackling temerity. Which is why it’s fascinating that, twenty-five years on, the person who arguably defines the Scream films is not Sidney at all—no matter who Ghostface happens to be calling.

[Spoilers for all five Scream movies.]

The very first Scream sent up slasher films of the ‘70s and ‘80s with humor and cleverness, and there at the center of everything was Gale Weathers—an ode to tabloid journalism gone wrong in every possible way. Dressed in truly hideous ‘90s neon with padded headbands and hair streaks so bright and sporadic you’d assume they were intended to refract headlights on dark roads, Gale seemed thoroughly uninterested in the ethics of news mongering. She wanted her story and the notoriety that came with it.

Gale made a name for herself covering the murder of Maureen Prescott in the previous year because she entertained the idea that young Sidney might have fingered the wrong killer in her mother’s death. Throughout the movie, her desire to probe deeper into the killings at Woodsboro High is frequently framed as amoral because her methods fit that bill; using hidden cameras, looking for back exits to more readily harass traumatized teenagers, flirting with Deputy Dwight “Dewey” Riley so that he’ll be more inclined to take her along on his patrol. Coldcocking Gale after a heated exchange is a victorious moment for Sidney, a point in the narrative where the audience sees what their Final Girl is made of before she’ll have to face death again. It runs as a joke into the next movie, Gale’s unwillingness to let Sidney close for fear of that right hook.

Still, nothing can change two items of note: One, Gale was right about Sidney’s misspoken testimony that put Cotton Weary in jail for her mother’s murder. Two, Gale survives the night despite multiple attempts to off her, and also contributes to Sidney’s victory by shooting Billy Loomis (after being mocked for forgetting to take off the gun’s safety the first time). At the very end of the film, in the coming light of dawn, Gale stands on the lawn of Stu Macher’s house and begins staging her live broadcast. She’s been menaced, nearly hit by a car, crashed her own news van, gotten shot and left for dead, but the story closes on her fading voice.

By the sequel, Gale’s desperation for notoriety has worked in her favor; her book on the Woodsboro murders was a bestseller that was then adapted into a movie called Stab. No one is happy with her, least of all Dewey, who believes that she painted him like an inept child within its pages. When killings start up on Sidney’s college campus, they are both on hand to help, however, and their flirtation kicks up a degree or two. Again, Gale is there when Sidney confronts the killers, again she is shot and still makes it out alive. Only this time, she makes sure to stay with Dewey as he’s wheeled into an ambulance.

What started as a chance to thumb our collective noses at tabloid garbage morphed into a different sort of story—The Perils of Women Who Want It All. The ‘90s and early aughts were rife with this particular narrative, a cultural anxiety born of Working Girls and Ripleys alike. What, the stories asked us, if moving through the world career-first as a woman was a bad call? What if it made you cruel, callous, perpetually ignorant of all the wonderful things waiting right at the end of that suburban cul-de-sac? Wouldn’t Gale be much happier if she chose to slow it down, stopped chasing murderers and fame?

During this era of cinema, that was the story you expected. That alongside Sidney’s neverending Final Girl footwork, we would watch Gale Weathers learn to love, to soften up and make way for all the things that women are supposed to want. But then in Scream 3, we learned that Gale didn’t stay with Dewey after all; she was given the chance to go to Los Angeles and head up “Sixty Minutes 2,” an opportunity that bombed, but got her back where the action was. More Stab movies were made, and Gale went back to doing what she did best.

It’s here that a turnover begins to occur. Gale runs into Dewey, who is working as an advisor to Stab 3 on a set in L.A. and they wind up talking about what went wrong between them. When Gale admits that she couldn’t pass up Sixty Minutes 2 and her chance to be another Diane Sawyer, Dewey replies, “What’s wrong with just being Gale Weathers? I liked her!”

And that sounds like Dewey wishing that the woman he loves could just give up all those ambitious notions of hers, sure. But the rest of the film tells a different story, one where Gale helps the police to work out this new set of murders with some unexpected aid… from the actress playing her in Stab 3. Trailed by Jennifer Jolie, who keeps in character far too often to be healthy and gives her notes on how to “play” herself, Gale is treated to a better understanding of how other people see her—through the eyes of a woman who has been getting character notes from Dewey himself. “Gale Weathers… would find a way,” Jolie tells her as she helps break Gale into the studio archives to look for more clues.

By the end of Scream 3, Gale and Dewey decide to get married and try out their relationship to see if it can work. The fourth film takes place over a decade later, with Dewey now serving as Woodsboro’s sheriff while Gale tries her hand at writing fiction. But the town was never right for Gale, and it still isn’t—she’s suffering from writer’s block and feeling useless in her surroundings. The deputy is flirting with her husband nonstop. And then, of course, Sidney comes back to town and murders start up again.

Gale is adamant that Dewey allow her to help with the case despite being a civilian because, as she is always irked to have to mention, she literally “wrote the book on this.” When he refuses her help, she does her own digging with the kids at Woodsboro High and gets back to her old tricks, trying to set up hidden cameras at a Stab marathon the school’s film club throws every year. Unfortunately, that choice is what gets her stabbed, and puts her out of commission for the rest of the action… but she’s still the person who winds up noting the vital clue Dewey missed before Sidney gets killed by her own cousin.

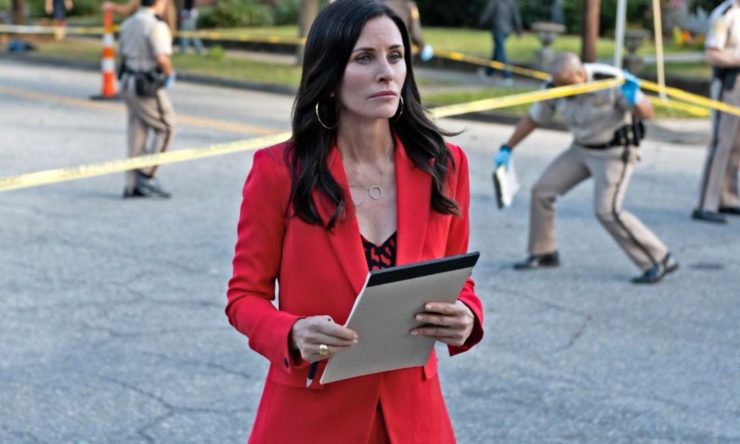

The fifth film takes us to a much darker place than any of the others, and we learn that Dewey was asked to retire as Woodsboro sheriff, presumably not long after he and Gale broke up. She’s the host of a national morning news show, which he dutifully watches every day just for the chance to see her face. When another set of murders begins, he tells both Sidney and Gale not to come back, but Gale arrives immediately and tells Dewey off for letting her know about all of this via text. Instead of another lengthy diatribe about Gale not being able to handle small towns, we learn that the fault of the breakup was his—they agreed it was Gale’s turn to pursue what she needed, and on moving back to the city to start her show, Dewey promptly panicked over the surroundings and ran home.

And there’s no blame, and there’s no malice. Just the truthful acknowledgement that they belong in different places, but that Dewey still should have told Gale why he left, so she didn’t believe it was all on her. He tells her that he hopes she’s still writing: “You were always happiest when you were writing.” And this isn’t wishful thinking on Dewey’s part again, but unfiltered truth—writing a book about a series of murders isn’t the way one would usually go about reporting that sort of news, but it’s what she prefers. She even once let slip that she planned to win the Pulitzer Prize one day, which is not something that you get for broadcast journalism. Gale Weathers is a writer, and this is what she knows how to write about.

Buy the Book

And Then I Woke Up

While Gale is reporting on the latest murder, Dewey goes with a young woman to check on her sister, who’s all alone in the hospital. He never sees Gale again because his legacy character status and multiple stab wounds have finally caught up with him. Sidney arrives and meets Gale in the lobby of the hospital and the two women wrap each other in a fierce hug. There is nothing but affection and respect between them now, and grief for the person they’ve both lost.

Gale tags along with Sidney to locate and stop the new killers, at another teen party in a familiar house. Gale gets shot again, and has to fight with murderers again, and listen to their unhinged plot again. Gale lives again. Because of course she does. You can’t do this without her, and more importantly, why would you want to?

Perhaps they’ll make more Scream movies down the line, and someone will finally take an opportunity to get rid of her. But that will be a mistake—because Gale Weathers is better than any Final Girl. She’s the one who never has to be here and always chooses it anyhow. And that means something very different than being chosen by fate and forced to reckon with the broken nature of things. When you’re Gale Weathers, you show up because you can do something about it, and because you’ve got too much ambition and nowhere else you’d rather put it, and because being a stone cold bitch is a compliment, actually. And it doesn’t matter how many people tell you that it’s none of your business, or that you should try being a little smoother around the edges, or that you hurt their feelings.

You’ve already written the book about this. They should all step back and take a few lessons.

Originally published January 2022.

Emmet Asher-Perrin didn’t appreciate Gale enough as a child, frankly. You can bug them on Twitter, and read more of their work here and elsewhere.